Harvested Wood Products accounting comes to Canada’s National Inventory Reports

To start with a guessing game, imagine Canada’s greenhouse gas profile and think about the TOP3 polluting sectors. Clearly, the Oil and Gas Industry and Transportation are in the TOP3, but which is the third sector at the top of Canada’s profile…? Electricity generation? Energy Intensive Industry like Aluminum or Steel? (Well, I realize the title of this post is a bit of a spoiler, but otherwise) I bet you wouldn’t have guessed that one right, right?

Every year, Canada (as well as all other rich countries) have to submit reports to the United Nations climate agency, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, detailing how much greenhouse pollution they have emitted in the year that ended about a year and a quarter before (e.g. in April 2015, data for 2013 is submitted). This year, a bunch of carbon accounting practices have changed, including this one:

One of the bigger and important accounting change in the 2015 National Inventory Report (NIR) is around the issue of Harvested Wood Products (HWP). Climate Action Network fought long and hard against this weird accounting practice back before (and during) the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009 but ultimately lost. In a nutshell, the thinking behind HWP is the idea that strictly speaking the carbon that is stored in trees does not get released to the atmosphere when the trees are cut down (or “harvested”) but only when the HWPs are destroyed/combusted. Think lumber for building or furniture: the carbon actually continues to be stored; just not in the tree trunks but rather in the lumber frame of houses or in the chair you’re sitting on. Or books: the carbon is now on your shelf. The problem with this of course is that the tracking of the carbon in paper or 2x4s is not particularly reliable, to say the least, so any inventory of HWP emissions rely heavily on models and their assumptions unlike cutting of actual trees, which can be measured directly.

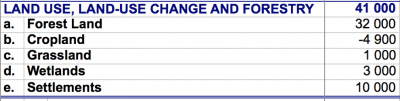

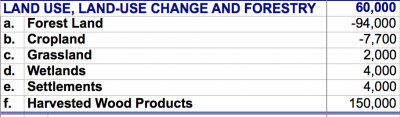

Amount-wise, this is pretty huge. Looking at the 2015 NIR that Canada submitted last Friday, the HWP emissions for 2012 were 150Mt CO2, or over a quarter of Canada’s total CO2 emissions that year (or roughly a fifth of CO2eq). Comparing these 2012 numbers from the 2015 NIR to those from the 2014 NIR (where HWP accounting wasn’t used yet), allows us to see the impact of HWP accounting on the entire land use, forestry and agriculture (LULUCF) sector (there are other changes too, but HWP is the biggest one): in NIR2014, the LULUCF total for 2012 was 41Mt, in NIR2015 the total for the same year is 60Mt. However, looking at Forest Land, this has flipped from being a 32Mt emissions source to a 94Mt carbon sink, most of the difference now being captured by the somewhat hard-to-understand HWP sub-sector, which is now an emissions source (in 2012) of a whopping 150Mt (see images below for a comparison of the 2014 and 2015 tables for LULUCF emissions in 2012). That’s not a small number! In fact, it makes HWP the third largest sector of the Canadian economy by amount of greenhouse gas emissions, after Oil and Gas extraction and Transportation!

I think the main problem with this change is transparency and accountability: it’s pretty easy to conceptualize forests as an emissions source (more trees chopped down than growing, releasing more carbon than they suck up) with pretty clear and easy leverage points for policy interventions. Further, this accounting change turns the forestry sector from a source into a sink, as a result of which we might conclude that the forestry sector is doing quite well and lose sight of it as a sector in which we need to change practices and policies as part of our overall climate mitigation strategy – not a good idea! On the other hand, it is plausible that HWP accounting makes visible possible leverage points for policy interventions there; e.g. around lumber recovery for construction sector, paper/wood fibre recycling etc to get emissions from that sector down…